November 18th, 2025

Capitol News Service 11/13/25

A handful of sheriffs are enforcing immigration policies so aggressively that they’ve put Maryland ahead of most red states in transferring migrants to ICE custody. It’s part of a local-federal partnership known as 287(g)

Sheriffs in Maryland are assisting President Donald Trump’s administration in carrying out his immigration policy at a faster clip than almost every other part of the country.

Maryland sheriffs have transferred at least 119 people from their local jails to Immigration and Customs Enforcement since Trump’s inauguration back in January.

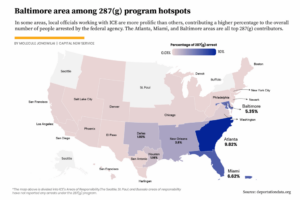

That number represents about 5% of all the people ICE has arrested in Maryland during that time – a higher rate than in any other part of the country other than a stretch that includes Florida, Georgia and the Carolinas.

What’s more, just three sheriffs are driving the trend in Maryland. Together, Frederick, Harford and Cecil Counties are jointly responsible for the 119 transfers from county jails to ICE under a cooperation agreement with the federal agency known as the “287(g) program.”

The findings are part of an analysis by Capital News Service and the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism at the University of Maryland, using government records collected by the Deportation Data Project.

Under the 287(g) agreements, local correctional officers in Maryland act as deputies of ICE, alerting the agency to migrants in their jails, and holding them until federal agents take them into custody. The program’s name references the part of the law that authorized it in 1996.

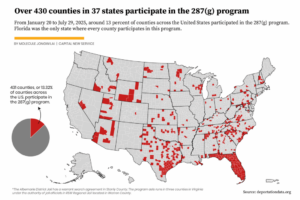

Since Trump took office again this year, a 287(g) fever has swept the country. Many sheriffs are scrambling to align themselves with the president’s immigration agenda, and the number of participating counties has grown by almost four times.

Perhaps most surprising is that Maryland – a blue state with Democratic leadership – would be at the leading edge of this trend. But the movement is driven by law enforcement officials in some of the state’s conservative-leaning counties. Five Maryland counties have signed the ICE agreement since January. And the arrest numbers in the counties that already participated in the program have spiked dramatically. The increase showed up in the first few days of Trump’s tenure. Maryland arrests doubled in the first six months of the administration, when compared to the same period the previous year.

“It’s really at odds with the trends that we see in the state,” said Naureen Shah, director of government affairs for the equality division of the American Civil Liberties Union. “Many people oppose what ICE is doing. The state has limitations on immigration detention, and generally people believe that they live in a state that is pro-immigrant justice. So the continued participation in the 287(g) program by these sheriffs is really out of step with where the state is going.”

But Frederick County Sheriff Chuck Jenkins said the program has led to lower crime rates.

“Look at how good things are here in Frederick County. It really is a land of pleasant living as far as not a lot of crime, not much violent crime whatsoever,” Jenkins told CNS. “We don’t have the numbers of criminal gangs … A part of that is due to the fact that we have worked with ICE over these years to get the criminals out.”

By far, Frederick is the leading driver of the Maryland numbers, accounting for 64 of the 119 arrests. Harford County accounted for 45 and Cecil County for 10.

Officials in Allegany, Carroll, Garrett, St. Mary’s and Washington Counties all signed the 287(g) agreements after Trump took office, but their numbers are not yet reflected in the ICE arrest database that CNS analyzed.

“Sheriffs are political animals in many parts of the country, and they want to be seen to be hand-in-glove with the Trump administration,” said Shah. “These people want to make a name for themselves as taking part in the biggest deportation drive in our nation’s history.”

That drive might help explain a sharp uptick in immigration arrests around the country recently.

But some sheriffs have been doing this for years.

Enthusiasm for the Cause

Sheriff Jenkins’ efforts are the most controversial in the region. Frederick boasts a high rate of arrests and, in Jenkins, a larger-than-life local leader. He proudly claims to have the longest-running program in the country, dating back 17 years.

But his work is also a magnet for criticism by advocates who say the county sheriff’s office displays a pattern of discriminatory behavior. In 2023, the ACLU asked the Department of Homeland Security to investigate Jenkins for “his misuse of office to stoke anti-immigrant racism.”

A 2021 settlement directed the sheriff to apologize, in writing, to a Latina woman who was improperly detained by Frederick County deputies. The officers claimed she had a broken taillight, according to court documents, and attempted to hold her for ICE.

“Data suggests that racially disparate policing is happening, racial profiling is happening,” Shah said. “I think it has to do with the culture all the way at the top of the sheriff’s office.”

But Jenkins’ enthusiastic participation isn’t wavering.

“I believe that we’re a safer county because of it. It’s been very effective in getting criminals off of our street, not releasing back onto the street, but turning them directly over to ICE,” he told CNS in an interview.

“I’ve hung my butt out there,” he went on. “I’ve been attacked politically for it, but I’ll stand by it, it’s been one of the best things we’ve ever done here in Frederick County.”

The recent uptick in ICE arrests around the country, he said, could have been preempted by the 287(g) program.

“You had to know this was going to come at some point,” he said. “Had everybody been doing what we’re doing and just methodically working with ICE in this partnership, turning criminals over to them for deportation, we wouldn’t be here today. I’m convinced of that.”

Jenkins acknowledges that the broader political leanings of Maryland are at odds with his program.

“Listen, it’s a Democratic-controlled legislature, Democratic state,” Jenkins said. “You have forces in politics that want to make Maryland a sanctuary state. I’ve been fighting this battle by myself for 18 years until recently.”

About 80 miles away, Sheriff Jeff Gahler of Harford County has a similar take. Gahler and Jenkins both testified back in March against a Maryland bill that would have banned 287(g) programs for the state.

Gahler says collaborating with ICE protects the public.

“Any program that allows us not to open a jail door and put a criminal, or someone who’s been arrested for a crime . . . back into the community, is public safety,” he told CNS. “I’ve said in many interviews – my responsibility is the borders of Harford County.”

But the Howard Center analysis found that the number of violent offenders transferred to ICE by Harford County since Trump took office is small. Many do not have prior criminal records.

In fact, more than 40 percent of the people Harford County has sent to ICE since Trump’s inauguration have been transferred before their local cases could be adjudicated. Some have had bench warrants issued against them because they’re in ICE custody and can’t answer local summons to appear.

There’s a range of views to the contrary across Maryland. The state has 23 counties, and only eight of them participate in the program.

Some counties have had buyer’s remorse. The county executive in Anne Arundel County signed on in late 2017. Around a year later, a new executive came into office and quickly reversed the decision. He’d received complaints from both public safety professionals and constituents, he said in an open letter earlier this year.

Citing potential legislative action around 287(g) programs, some counties are holding off – for now. Wicomico County officials had been debating entering into a 287(g) agreement, but recently decided to table the controversial proposal. A coalition of advocacy groups, including the ACLU of Maryland, Wicomico NAACP, Crabs on the Shore, Comité de Apoyo a los Trabajadores Agrícolas, CASA, Word of Life Center Immigration Services and local community members, spent months organizing against the program.

But County Executive Julie M. Giordano said the county board still wants to enter the agreement and only paused to address some internal concerns. One of those concerns was the issuance of new guidance from Maryland Attorney General Anthony Brown that Giordano calls “threatening.” The new guidelines remind local law enforcement agencies of the limits for cooperation with federal law enforcement.

“Maryland officers remain bound by Maryland law and standards in nearly all circumstances,” Brown wrote, “even if different policing standards are applied by federal law enforcement agencies.”

Around the state, sheriffs who don’t participate question how much the program helps – or hurts – their work.

Maxwell Uy, the sheriff in Montgomery County, doesn’t technically oversee a jail, so he wouldn’t be able to participate in the program like other sheriffs in Maryland.

But he argues participation in the program might damage the relationship between law enforcement officials and their communities. He says immigrants are more likely to be victims of crimes.

“If we erode that trust, we could potentially have a situation where our immigrant community is not reporting crimes or seeking services,” he told CNS. “With 1.1 million residents and a wide range of socioeconomic statuses and a wonderfully diverse population, if we have fear about our law enforcement community, we will not be able to respond to crimes.”

A NOTE ON METHODOLOGY

The findings in this story are results of an analysis by Capital News Service and the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism at the University of Maryland, using government records generated by the Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency. The records have been collected by the Deportation Data Project, a repository of immigration enforcement information at the law school of the University of California, Berkeley.

The review analyzed arrests between Trump’s inauguration on Jan. 20 and July 29 of this year, breaking them down by the ICE agency’s “areas of responsibility.” The Baltimore Area of Responsibility encompasses all of Maryland, but other areas encompass more than one state. The Atlanta area, for example, includes Georgia, North Carolina and South Carolina.

The data is current as of July 29. This reflects the latest records released by ICE to the DDP in response to a Freedom of Information Act request. The number of arrests is likely higher; updates have been delayed, in part due to a government shutdown, but spotty, more recent records obtained by CNS from local sheriffs’ offices suggest a continued rise.

The figures reported here represent the percentage of total ICE arrests since Trump’s inauguration through a federal-local partnership known as a “287(g) agreement,” which lays out how local law enforcement agencies may cooperate with ICE to enforce immigration law. The name is a reference to the subsection of federal law that created the program in 1996.

Local officials across the country follow different models of cooperation, but in Maryland the participating counties follow either the “Warrant Service Officer Model” or the “Jail Enforcement Model.” This means local correctional officers monitor their jails for undocumented immigrants and may transfer those immigrants to ICE custody. Police won’t go out in search of immigrants in their field work, however.

The analysis found that Frederick, Harford and Cecil Counties led in 287(g) custody transfers, together totaling 119 transfers to ICE. Other reporting by CNS suggests that the other Maryland counties newly implementing the program have also made 287(g) arrests, albeit at a lower rate, but those numbers are not yet included in available ICE data.